On Black admissions & retention...the revolving door

“We became very vocal with regards to African American causes. We understood, during the 80s, what we identified as a revolving door of the African American student experience. The university would admit in many African American students that may not be completely qualified on paper to be able to survive and would not provide them with the necessary support, to be able to matriculate through the system. It became a revolving door. They would bring them in, they would get the funding for them, they would not give them the social support and the educational support that they needed. Then they would kick them back out and they would not matriculate through the system. They’d bring in a whole new group and start doing the same thing.”

ORAL HISTORY TRANSCRIPT

Audio Recording

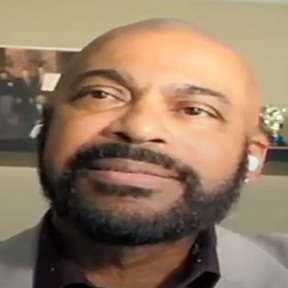

Interview with Daryl Jones (1984-1987)

Interview Date: August 9, 2021

Interviewer: Francena Turner

Method: Zoom recording

Length: 39:41 minutes

Transcription software: otter.ai

Transcription edited by: Francena Turner

NARRATOR BIO: Daryl Jones transferred to the University of Maryland, College Park from the University of Maryland, Eastern Shore in 1984. He graduated in 1987 with a degree in history. While at the University of Maryland, College Park, Jones led a charge to reactivate the defunct campus NAACP chapter. In this capacity, Jones along with the presidents of the African Student Association and the Black Student Union and other student organizations led several student actions aimed at convincing the university system to divest their interests in South Africa. Jones and other student leaders also organized around Black retention and inclusion on campus. After graduating, Jones attended the University of Baltimore Law School and served as a prosecutor and worked in private practice before becoming the Board Chair of the Transformative Justice Coalition, a national organization that “seeks to be a catalyst for transformative institutional changes that bring about justice and equality in the United States and abroad.”

KEYWORDS: University of Maryland, Eastern Shore, Glen Burnie, MD, transfer student, National Association of Colored People (NAACP), Black Student Union (BSU), African Student Union (ASU), Divestment Movement, South Africa, shanty towns, marches, student organizing, student activism, Main Administration Building, Louis Farrakhan, Kwame Ture, Laurie Harris, Mariola Nzumah, Lonta Evans, Ed Martin, McKeldin Mall, Administration Building, Homecoming, Otis Williams, Caroline Hall, Ritchie Coliseum, Kim Judd, Congressman Tom McMillan, Joyce Ann Joyce, Dick Gregory, Nyumburu Cultural Center, Alpha Phi Alpha, Testudo, University of Boston Law School, Transformative Justice Coalition

Francena Turner 00:00

Mr. Jones, I want to thank you for agreeing to do this interview with us today. My name is Francena Turner and I’m conducting an oral history interview with Daryl Jones for the Reparative Histories and the Black Experience at UMD Oral History Project. Mr. Jones, I want to start with what’s your hometown?

Daryl Jones 00:26

My hometown is Glen Burnie, Maryland.

Francena Turner 00:28

Okay, and what’s your birthday?

Daryl Jones 00:31

My birthday is July 20, 1964.

Francena Turner 00:35

How would you describe your life before you came to UMD in terms of family composition, education, things of that nature?

Daryl Jones 00:44

Oh, very positive. I came from a family of educators. My grandparents were educators, my parents were educated, college educated, and my sister, brother, everyone. It pretty much was expected to go to college. Growing up it was just not something that was unexpected. That was expected for us. As we moved along throughout our grammar school and secondary school, post high school, obviously, we were expected to go to college.

Francena Turner 01:24

How did you make the decision to go to the University of Maryland?

Daryl Jones 01:29

I did not start at the University of Maryland, College Park. My sister was the eldest of three children; she selected Maryland. She went to Maryland first during the ‘70s. After that, when it was my time to go and select the university, I was looking at various colleges. And my mother, who went to University of Chicago, wanted me to go to an HBCU because did not have that opportunity. Because her parents… she was out of the Chicago area. She was instrumental in me selecting the University of Maryland, Eastern Shore to begin my college experience so that at least one of her children would have gone to an HBCU. While I was at Maryland, Eastern Shore, I decided, after my second year, to transfer over to the University of Maryland at College Park. That decision was brought about because I felt as though I had gained a lot from the University of Maryland, Eastern Shore and my professor, my guidance counselor at the time, had encouraged me to move over to the University of Maryland, College Park from the University of Maryland, Eastern Shore feeling as though I would get a much broader experience at College Park.

Francena Turner 02:46

And what year did you transfer over?

Daryl Jones 02:49

- I transferred over to College Park. So, ‘82 to ‘84 I was at UMS and then ‘84 to graduation ’87, I was at College Park.

Francena Turner 03:01

How did you go about selecting a major?

Daryl Jones 03:06

Hmm, interesting question. I had always had a very keen interest in history. And so my major throughout my college undergraduate career was history. At Eastern Shore, I majored in history and then once I transferred to College Park, I majored in history and then concentrated in Latin American Sudies but staying in the liberal arts arena.

Francena Turner 03:43

Walk me through, if you can, your earliest memories of coming on campus as a new student.

Daryl Jones 03:52

Coming on campus to College Park as a new student, from my perspective, was very different, and that’s because I came from the perspective of initially going to University of Maryland, Eastern Shore. My initial entree onto Eastern Shore, I had no idea no concept of what a predominantly African American college or university would look like. Because everything I had experienced, I was always one of maybe two African Americans in my classroom from first grade until I graduated from high school. Initially, going to Eastern Shore, where it was the exact opposite of what I had experience was really just an eye-opening experience. So having gone through two years of college, having experienced that, and being so well indoctrinated into the African American History and African American experience, I then transferred over to College Park where again, I was transposed to a situation where I’ve again became a minority population within the larger university context. Walking onto the campus, rather than having the unsighted experience of understanding a lot of the Black cultural experience from the University, Eastern Shore, I was now awakened and alert as to differences in how people were perceived, how people were treated, and the demands that should be made for equality and treatment. Walking onto College Park’s campus, I already had that heightened awareness that had been instilled on, in me. Once I got to College Park, I immediately went into the mode where I was identifying with the African American students that were there and trying to be certain that we had a core group of people that were supportive of one another, and that proved to be really instrumental. While I was there, we actually restarted…the president actually restarted the NAACP chapter at the University of Maryland College Park. I can recall that once we started this NAACP chapter, we then formed an alliance and affiliation with the Black Student Union, as well as with the African Student Union. It was a very strong alliance during that period. There was so much that was going on, and this would be the early ‘80s. At that point, the University of Maryland was still investing in companies that were doing business in South Africa during the apartheid period and we got together–the student leaders, the presidents of those three major organizations got together—and built shanty towns and took a stand to demand that the university divest from its interest in South Africa. There was a lot of that, that went on, and we were in place and marching on the administration, the president’s building, demanding that they do this, demanding that they that they step it down. We brought Louis Farrakhan on the campus to talk about it, we brought Kwame Ture onto the campus to talk about it. We had a lot of a lot of activity that we were a part of. We became very vocal with regards to African American causes. We understood during the 80s, what we identified as a revolving door of the African American student experience, where the university would admit in many African American students that may not be completely qualified on paper to be able to survive and would not provide them with the necessary support, to be able to matriculate through the system. It became a revolving door. They would bring them in, they would get the funding for them, they would not give them the social support and the educational support that they needed. Then they would kick them back out and they would not matriculate through the system. They’d bring in a whole new group and start doing the same thing. Part of what we tried to do was to be the stop in the door–that doorstop–to say, “We’re not gonna let this door revolve.” What we wanted to do is build an infrastructure that’s in place to support the students that are being brought in, so that they can certainly have the opportunity to learn what university life is like and understand the stresses that are associated with being a Black student at the University of Maryland, College Park, and how to cope with survive.

For the full transcript, please email university archivist, Lae’l Hughes-Watkins at laelhwat@umd.edu.