On choosing acting over football

“A new coach comes in, and he says, “Okay, Holliday, I hear you’re quite a character. I said, “Well, yes, sir. I enjoy playing football very much at the university. But right now. I’m doing a major stage production for the drama department. I’ve moved my major to Speech and Drama education.” He says, “Well, what does that mean?” I said, “Well, there’s no understudy for me. I will only be able to play one week of spring football.” It was two weeks at that time. The next thing on his mind was “Well, Holliday, you don’t have to worry about playing football at the University anymore. You can keep your scholarship and all the benefits, but you’re not going to be playing football anymore.” I put on the long face. I’m taking acting anyway. [laughs] I put on the long face thing, “Oh, wow. Oh, no. I can’t play football no more.” Inside, I was saying, “Thank you, Jesus. Thank You, Lord, you have delivered me!”

ORAL HISTORY TRANSCRIPT

Audio Recording

,

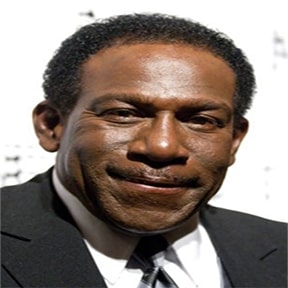

Interview with Kene Holliday (1967-1972)

Interview Date: August 6, 2021

Interviewer: Francena Turner

Method: Zoom recording

Length: 74:50 minutes

Transcription software: otter.ai

Transcription edited by: Francena Turner

NARRATOR BIO: Kene Holliday came to the University of Maryland, College Park in 1967 from Amityville, NY and graduated in 1972 with a degree in speech and drama education. Kene went on to have a long and award winning career in theater, film, and television acting and theater directing. A founding member of Folger Shakespeare Library’s Folger Theatre Group and the D.C. Black Repertory Theatre Company.Holliday also currently works with the Negro Ensemble Company of New York City.

KEYWORDS: New York City, NY, Amityville, Long Island, track, football, Bob Ward, Roger Meersman, racism, sports injury, Eugene Oneil, William Bendix, The Hairy Ape stage play, Dim Montero, football player strike, Drama Department, Speech & Drama Education, Tawes Fine Arts Theater, Imamu (Amiri) Baraka, Don L. Lee, Janifer Baker, Karla Witcher, Belinda Cooper, and Jay Stewart, Motojicho, Vantile Whitfield, Folger Theater Company, Richmond Crinkley, Robert Hooks, DC Black Repertory Company, Thomas Starcher, interracial dating, Rudy Pugliese, John Sartre, segregation, Fraternity Row, Student Union, Earl Wynn.

Kene Holliday 00:00

I gotta take those off.

Francena Turner 00:04

My name is Francena Turner and I am conducting an oral history interview with Kene Holliday.

Kene Holliday 00:14

I would prefer if you pronounce it Keen. K-E-N-E.

Francena Turner 00:25

I’m conducting an oral history interview with Kene Holliday for the Reparative Histories and the Black Experience at UMD Oral History Project. Mr. Holliday, the way this is structured is I’ll ask you some questions about your life before UMD, we’ll talk about your time at UMD, and then a little bit about your experiences since UMD.

Kene Holliday 00:48

What does the B stand for?

Francena Turner 00:50

- UMD.

Kene Holliday 00:54

Okay. No problem. Because we used to have a ton of satellite colleges that were part of the university system. Okay, you go right ahead.

Francena Turner 01:09

Okay, what’s your hometown?

Kene Holliday 01:12

I’m from New York City, New York. I was raised in a place called Amityville, Long Island.

Francena Turner 01:22

And what’s your birthday?

Kene Holliday 01:25

6-25-1949

Francena Turner 01:29

How would you describe your life before you came to College Park? In terms of your family composition and that kind of thing?

Kene Holliday 01:41

By the way, do you have enough light on me?

Francena Turner 01:46

Yes, I can see.

Kene Holliday 01:48

Okay, fine. I was a high school athlete and somewhat of an academician, but I wasn’t one of the A+ guys. I usually hovered around the B+. My athletics were extraordinary. I was an All-Long Island football player. I was a running back. I scored a lot of touchdowns and played really serious football. I also was the track star, 100 yard dash champion, county champion in 100 yard dash in my junior year and I was on my way to repeating that in my senior year when I pulled a hamstring in one of the preliminary events. That kind of took me and my relay team out of the running there. I had established such a great reputation in my athletics with the football and the track the prior year, and my academics were in very good shape for recruiting process prospects. I was recruited by schools all over the Northeast, even the military universities were trying to recruit me–Annapolis and West Point. I decided I wanted to leave the New York area because I was tired of the cold weather. I played football and sometimes the ground was as hard as a concrete street. I decided I wanted to go someplace that was more climate friendly.

A gentleman from the University of Maryland contacted my coach and asked if he could interview me. Raffiele was his last name. I miss his first name, but Mr. Raffiele interviewed me and he came to my home to talk to my mom. My father passed away when I was 12. He was a United States Navy veteran–14 years of service in World War II. They set up a visitation for me to come down to the university and have a visit, and I did that. I got down there and the weather was so nice. It was really nice weather and the school was enormous and incredibly impressive. They were telling me, they said “We have 24 colleges housed here in this university. So anything that you want to study, we more than likely have it here.” They took me downtown. They said, “By the way, we are only six miles away from the Washington DC border, so we’re going to take you on a little tour.” They took me downtown onto Pennsylvania Avenue, and they parked the car. I said, “What’s this?” They said, “Well, just watch.” We’re sitting there, and I’m like, “Well, what’s going to happen?” It’s about three minutes to 4pm. At 4pm, the street became flooded with people leaving the offices down there. These were other senior football players saying, “Now take a good look. What do you see?” I said, “I just see tons and tons and tons of women.” He said, “Exactly. In Washington, DC there are 14 women for every man.” I said, “Really? Guys, I think you got a deal!” They took me and signed up. That was the beginning of my journey to the University of Maryland. It was the fact that it was so close to Washington DC and all these beautiful Black women.

[brief technological interruption]

I was very excited about going to the University of Maryland and also to play football because they had a coach named Lou Saban. Lou Saban coached the Buffalo Bills up in New York with OJ Simpson, and people of that nature. He was an advocate of what was called the modern pro football formation. This was run and gun, throw the ball down the field to these guys that are fast and speedy, they catch it, run it in for a touchdown. That’s what I like to do. I like to get the ball running and run a pattern down the side of the field, catch the ball, take it in for a touchdown. So I thought, “Oh man, I think this is great. This guy is gonna be a pro football player.” That was my original concept of what I was going to do. “I’m gonna play pro football, because I got Lou Saban. Coach me.” Little did we know before we arrived for our summer training session, Coach Lou Saban had resigned his post at the University of Maryland and moved on to the Denver Broncos to prepare the way for the coming of John Elway. They gave us another coach who was a former All-American. Bob Ward was going to be the head coach. And Bob Ward’s philosophy of football was what we called ground and pound–three yards and a cloud of dust and you take the ball. We wound up with Bob Ward–a completely different philosophy of football. At that time, I weighed about 185 pounds. I was a speed player, not a ground and pound kind of guy, give him the ball running into the middle of the pile there, and try to dig out three or four yards at a time. This did not work well with me.

Also, this was the University of Maryland. I had been warned that you’re going down right there below the Mason Dixon Line Holliday. Do you know what you’re getting into? I say, “Well, I can handle it. I’m from New York. I can adapt to anything.” There was a great deal of racism that I was dealing with with some of the players. In these days, they hadn’t played with black players before. We only had a few Back players on the team. Some of them were still carrying their very racist training that they had grown up in. It was difficult sometimes. Sometimes I would be running the end, I’d point to a guy that I wanted my split end to block, and he’d turn his head and look the other way and make believe he didn’t see that guy. It was very difficult. We all lived in the same dormitory. They had a high rise dormitory. This was very nice. Varsity lived on the eighth floor, the junior varsity or freshmen team lived on the seventh floor. There was a lot of stuff that would go on that was racially racially motivated. The coaches did nothing to absolve this because some of them were still operating on a racist mentality as well. By the end of my freshman year…

Francena Turner 12:28

What year did you enroll?

Kene Holliday 12:31

I enrolled in fall 1967. In that freshman year, I was decidedly unhappy. My academics were fine. I had one instructor…I’ll tell the story a little bit later on, because I’m getting ahead of myself. I decided I was going to stay and make varsity. I wanted to get my varsity accreditation. I stayed into my sophomore year. I played and we were terrible. My freshman year was wonderful because we had a coach named Dim Montero and Dim Montero was the equivalent of Knute Rockne who created the game of football supposedly. Dim knew everything. He had been a coach at a boys prep school where young men would go to prepare to fix their academic status so that they could get scholarships to go play football elsewhere. Dim had a record of something like 640 wins and 14 losses. He was a wonderful old guy. We loved him dearly. It was like your grandfather was out there coaching the team. Dim was a nice man; he understood what we were going through–the Black players–and he tried to talk to those guys about us being a team, as opposed to some type of racial dichotomy going on. We won every one of our games as freshmen because Dim was just brilliant. He could make one change and the tide of the game would swing. We loved Dim. We loved playing for Dim because he let us play the game that we were recruited to play which was to throw the ball down the field, run the end, and speed, speed, speed speed. That was a great time for us.

But when we got to varsity, it all changed and it turned into ground and pound, and they had some coaches that were decidedly racist. I had one coach, he literally, one day, made me get injured. I had an afro going on there in the late ‘60s and pre ‘77– a big huge afro. I was from New York, and they had problems with me and my mouth. I wasn’t one of those “yessuh” guys, and all that. I didn’t do all that. “I’m from New York, man, what do you want? What do you want? You want something? Let’s talk about it.” They didn’t appreciate that kind of mentality very well. I played that sophomore year, and I played enough to be eligible for my varsity letter. I got into some stuff there with one of the coaches. He was the linebacker coach, and he liked to do things to the Black players. He would run players off. Basically, they looked at me like I didn’t fit into the program, and they were trying to run me off. I’m from New York, and I said, “I’m not going anywhere till I’m ready to go somewhere. Right now I’m not ready to go anywhere.” One day, he decided he was going to make me an example. He had me holding what they call blocking dummies. It’s like a big pillow, but it’s made out of the material that they use on trampolines and things like that. It’s very, very, very durable. Guys come to hit you with it and you just brace yourself and they will bounce off of it and you don’t get hurt. We’re doing a blocking exercise and he decided that I’d hit the guy back with the pad. He was trying to hit me hard. I hit him back and he bounced off me. This is the coach and this is a critical moment. He starts talking to me real bad, real bad before everybody like I have done something incorrect. You see, this is football and I’ve learned that you have to protect yourself in football. You don’t let somebody hit you in football. He told me that I should not hit back; I should not defend myself. They tried to hit me again and I defended myself out of instinct. I bounced this guy again. Now he’s really mad. Now he tells me, “If you don’t just stand there we’re going to have a problem.” What he was talking about was that he was going to have me kicked off the team. I stood there and they switched guys. They put in the captain of the team. Guy’s name was Labrewski. They put him on the line there and Labrewski was about 245 pounds. He just blasted me. When he blasted me, my right shoulder was incapacitated. He almost broke my collarbone, but my shoulder was totally injured. I had to leave the field and go to the trainer. I tell the trainer what happened and the trainer says “That son of a bitch.” Because they did this to other Black guys. It took me somewhere around four years before I could throw a baseball again with that right arm. That’s how bad the injury was; it was all discordant. At that point in time, that made up my mind. I’d had it plus the fact we weren’t winning. We were 0 and 8 in my sophomore year on the varsity. I just had enough.

I started thinking about doing something else. With my scholarship, I had a lot of classes that I could take to just experiment to see if I wanted to be a part of those classes. I liked theater because my grandmother used to take me to Broadway shows on my birthday every year. I decided I want to go into an arts class. I took a seminar in the history of theater. Lo and behold, I liked it. One of the tutors from the football team was the grad assistant. The word was, if you attended class, you would get a C, if you attended class and did your work, you would get a B. If you did some studying and attended class, you were going to get an A. I got an A, which was great for me, because it helped me stay eligible to play football. If you didn’t maintain the 2.5, you couldn’t play and that would give them a reason to drop you from your scholarship. I took that class; I aced it. I liked the class, I liked what I was seeing. I learned a tremendous amount about the beginnings of the theater in the world, and the art that goes into it. I decided to take a beginning acting course that spring. I took Acting 001. And the instructor was a gentleman by the name of Roger Meersman. I’m in Meersman’s class and Meersman was delighted because I had some background from my high school days In Shakespeare. I understood Shakespeare and what Shakespeare was all about and how to speak the speech and understand what we were talking about. I did a few scenes in Acting 001 and Roger really liked it.

Spring time came and I was getting ready for spring football. Roger tells me, “ I got something I want you to do.” I said, “What do you want me to do?” He said, “ I want you to do this play.” He handed me a booklet and it said, The Hairy Ape by Eugene O’Neill. I had come to know that Roger was a very unusual professor in that he was an impressionistic director. He created images with the people that are on stage. That’s how he painted. He painted with people and their words. I said, “Well, let me do some study here.” Because I know Roger is not racist. He likes me. I became one of his favorites there, because I would do all the things that he was looking for in the classes. Roger had given me this script. I read the script. I read the history of the script , and on the inside cover, it said that this play debuted on Broadway with William Bendix starring as Yank, which is the role that he wanted me to play. Yank was the leader of a group of stevedores on an Atlantic crossing ship. They used to shovel coal. That’s how they kept the engines going back in the original days of the engines that they have. These guys were all muscle. [laughs] They were Neanderthals. They very much like Neanderthals. I recognized William Bendix’s name. William Bendix was the star of a television show called the Life of Riley. He was a star. I read this thing. read the piece, and I saw this tough guy, man. This is good stuff. This is my kind of deal. Perfect for a former football player. I wasn’t former at that point yet. I said if it’s good enough for William Bendix. I’m going to trust Roger Meersman to make it good enough for me–to make it salient and prosperous for me. I signed up. I started work on the play.

For the full transcript, please email university archivist, Lae’l Hughes-Watkins at laelhwat@umd.edu.